|

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Commenting on Two Maxims of Saint John of the Cross

Saint of the Day, Saturday, November 23, 1968 |

|

|

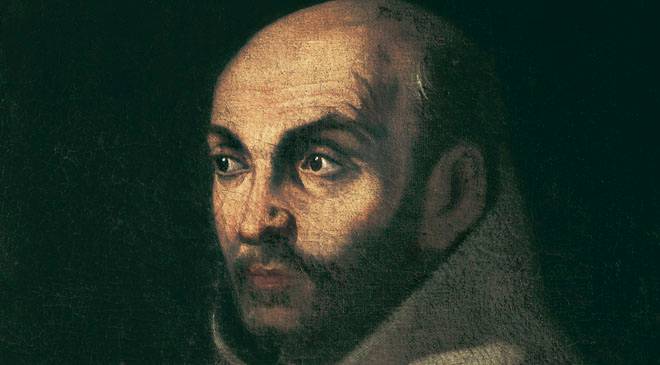

Saint John of the Cross (1542-1591) © P. Rotger/Iberfoto On November 23, there is no feast on our calendar. Tomorrow is the feast of Saint John Capistrano, confessor, and of Saint John of the Cross, confessor. As you know, St. John of the Cross was the great reformer of the Carmelite Order along with Santa Teresa of Jesus. She reformed the female branch of the Carmelites and was the mentor of St. John of the Cross for reforming the male branch of that Order. He is a Doctor of the Church, a Mystical Doctor of the Church because he delved in a marvelous way into all matters of the mystical life of the Church. I wish to comment on some maxims of Saint John of the Cross, and as his feast introduces us to a characteristically Spanish environment, I would also like to comment on one or two episodes of the Spanish Civil War, episodes of heroism mentioned in the text picked for tonight. Among other maxims, Saint John of the Cross says, “From little things you get to big ones, and the evil, which at first seemed insignificant, later becomes very great and without remedy.” This is an eminently counter-revolutionary, antiliberal, and ultramontane principle, and some of its applications make us understand well what it consists of. A liberal spirit is led to optimistically consider that everything will always go well and that we should be carefree, optimistic, and let everything go. There is no reason to interfere with events, except very rarely, because things rarely go wrong. Optimism is a trait of spirit inherent to liberalism and to naturalism. A naturalistic individual is one who does not believe in Revelation or the supernatural. Because he does not believe in Revelation or the supernatural, he does not believe in original sin or in God’s punishment. Whoever does not believe in original sin is an optimist. He thinks that all men are good, that everything will always go well, that things usually turn out well. He is shocked when something bad happens: how did that happen? How did so-and-so do such a thing? Who would have said such a thing would happen to him? That he would do such an evil deed? Since they have no concept of sin and do not want to hear about punishment, they are amazed at the evil when they see something bad happen to someone. Sometimes an 80-year-old man dies; when a liberal hears about his passing, he’s shocked: Wow, really? Don’t tell me! Why become shocked? Was he not mortal? It should not be a great surprise that a mortal would die! Even more so when you are at the age where you usually die. Sometimes you even need to prepare your mind because someone died. It is natural for an octogenarian to die. It would be a surprise if he lived. This is sheer reality. In the face of death, a liberal man is surprised. He is surprised even by his own death, as he does not imagine that he is going to die. He is surprised by epidemics and by all sorts of misfortunes because, for him, things turn out well; everything goes very well. The illiberal mind knows that the opposite is true; that man has within himself a great propensity for evil and that evil easily grows in his soul. So he needs only to consent to bad things just beginning in him for them to reach extreme evil quickly. Therefore, a consented bad look to, a consented bad thought or movement of revolt within the Group, a movement of bad mood or laziness during a lecture—no matter how stupid the speaker—can easily lead to extreme consequences. Where does the laziness movement lead? It leads us to listen unattentively to something that deserves attention. Do you know what that produces? It causes a hardening of the soul. The soul gets used to hearing important things and not giving importance. Nothing does more harm to a soul than to remain indifferent when faced with important, beautiful things of Catholic doctrine (regardless of who explains them). That causes acedia in the soul. St. Thomas Aquinas calls this a lack of appetite for good. This lack of appetite for good is the death of God’s love. The love of God dies by dint of remaining indifferent to things that come from God as we hear His doctrine, the doctrine of the Catholic Church, or have the opportunity to wisely examine events in the light of the doctrine given by God and the Church and, facing this examination, remain indifferent. Why? Because we are thinking of us. The lecture is unfolding, Catholic doctrine is being expounded, and I am thinking: how nice it would be if I were now on a plane, in a place, with everyone applauding me and this or that. The result is ever-increasing self-absorption and hardness toward God. Saint Augustine said that in the world, there are two cities, two types of men: those who carry the love of God to the point of forgetting themselves and those who carry the love of themselves to the point of forgetting God. Whoever belongs to the first type is from the city of God; whoever belongs to the second type is from the city of the devil. Anyone used to listening with indifference to elevated and noble things that do good to the soul is deep down thinking of himself and walking toward the hardening of the soul by which people belong to the city of the devil and evil snowballs. Everything in man that leads to evil immediately finds great resonances, consonances, and affinities. That is why, no matter how little we consent, it is already a flame, a fire that catches. So, Saint John of the Cross says very well: we must nip the evil in the bud right at the beginning; because we can do it without difficulty; later, it can become a massive fire. That is a principle of spiritual life and also a principle of government. That is how we should act with those over whom we have authority. For example, if we have a servant and we start giving him the freedom to joke around a bit, today he says a little joke, tomorrow an insolence, the day after tomorrow he revolts. Why? Because pride grows rampant. All defects gallop forward. If you want to keep that servant, the real thing to avoid big problems is not to put up with the little things but suppress them. Why? Because wisdom dictates that principiis obstat: it creates an obstacle to evil in its beginnings. Do not let yourself be carried away by the idea that evil is not very dangerous in the beginning, because it has its full strength and attacking force from the very beginning. When it comes to governing a country, you have on that wall the painting of a man who ignored this principle. Look at his face. His costume is beautiful, but his face is that of a perfect idiot, the optimistic face of a jolly fool. He did not suppress the French Revolution in its inception, and as a result, the French Revolution cut off his head. Pope Leo X failed to suppress Protestantism in the beginning. “Oh! it’s a quarrel of friars!” As a result, the friars’ quarrel tore Europe apart. We could make a sad list with the narration of events that took catastrophic proportions but could have been cut short when small. Nature also reflects this principle with beautiful symbols. Fires usually start small and are easy to put out, but they expand quickly. It is easy to set something on fire, but it is hard to put it out. It is not difficult to propagate evil even in the physical order; it is difficult to eradicate it. It is easy to inoculate someone with disease; the hard part is to cure someone of his disease. It is easy to become addicted. A person can become addicted to drunkenness in one evening. The hard part is to shed the vice. Therefore, the Catholic state of mind is this suspicious, vigilant state of mind that sees everywhere a nascent evil that can take huge proportions. Such is the Catholic, antiliberal, ultramontane state of mind enunciated by Saint John of the Cross. The bad state of mind is that of a happy-go-lucky, good-natured, cheerful, confident person who looks the other way and is betrayed by everyone. Everyone laughs at him, tricks him, and throws him on the ground. He deserves to be trampled underfoot because a man like that is disgusting in capital letters. One is disgusted with an improvident cretin, especially when it is a voluntary stupidity when, out of laziness, a man says: stupidity, you are my mother! And hugs it. This lack of wisdom is disgusting. Here we have a saint’s maxim teaching us otherwise. I am rereading it: “From the little things you get to big ones, and the evil, which at first seemed insignificant, later becomes very great and without remedy.” Here is another maxim: “There are many who do great things, but they are of no use to them because they seek themselves and not the glory of God.” St. John of the Cross lived in times of nobles and great orators. Woe to us who no longer have nobles or great orators! We have progressive priests and demagogues. He lived at the time of nobles and great orators, especially great sacred orators. Those nobles performed extraordinary acts of courage, as I told you yesterday about the Chevalier d’Alsace. Those sacred orators gave very long sermons because people would listen to three or four hour sermons. The speaker was placed in a very high pulpit so his voice could propagate throughout the whole church. At that time, there were no loudspeakers, and they took water and wine to the speaker and a towel on a small table. He would stop and dry himself to continue as everyone sat down. You have read [Fr. Antonio] Vieira’s sermons and know how long they lasted. His sermons were grand, excellent! We delight in them, but we do not sanctify ourselves. He gives true Catholic doctrine but we do not sanctify ourselves because he did great things, but not for God’s sake. As you know, he was a bad priest. . . . He once went to Holland to try to sell Pernambuco to the Dutch Protestants to give money to Portugal’s treasury. He was an evil man who did great things, but they were no use to him because he did not do them for the love of God. Vieira is gone. Scholars still speak of him; some happily indulge in reading his works. They are wonderful indeed for those who have enough anachronistic taste to appreciate them. But have you ever heard that someone sanctified himself by reading Vieira? Curiously enough, he has edifying thoughts that would be good for the soul. But they are useless. Those knights did extraordinary acts of heroism, but they were useless because they did them for themselves and not for God. They did it to show off. Can we derive any fruit for our spiritual life from this maxim? Do we sometimes do good things for others to see and not out of love for Our Lady? This is how we must examine ourselves: If those here doing an apostolate that others see were suddenly sent to do apostolate that others do not see, would they do it with the same enthusiasm? Yes or No? If yes, they are likely doing apostolate for the love of God. If not, they are not doing apostolate for the love of God, or, at least, there is self-love involved. When self-love mixes with the love of God, it drowns out the love of God. Imagine, for example, that tomorrow I came to one of you and said: “Look, Vietnam depends on your action to be saved, but no one will ever know. They’ll think you’re going to rest for six months in Campos do Jordão. You go to Vietnam, do some secret [apostolate] that no one will ever know, and come back after six months saying you were in Campos do Jordão. It is not a lie because you first go to Campos do Jordão and then come back from Campos do Jordão. No one will ever know. “Only I will know but will be unable to show you any consideration in front of others because they will perceive that you have done this or that. So your action will be valid only in the eyes of God and nobody else. Moreover, so that you do not draw attention to yourself later and people do not become curious to find out what happened, you will have to play an extremely humble role in the Group for your entire life. You will play the least possible role within the Group. But in God’s eyes you will have this consolation: you saved Vietnam.” Would you react like this: “O wonder! How kind God has been to me! Only Our Lady could do that! By receiving such a grace known to no one, I have two advantages: I serve Her and then have the joy of anonymity so only She and I know what I have done, and I will receive my reward in Heaven. For now, it will be her secret and mine. I will keep a secret with my Queen. I hope she implants the secret of Mary in my soul. I will live in the shadows, and no one will ever know. She alone will know, and I am at peace with my conscience.” Would we all immediately have that reaction? Maybe not. Imagine the opposite: “My dear friend, I am going to give you an apostolate that will be a tremendous ordeal: you will have to show up a lot. Mortify yourself.” “Of course, Dr. Plínio, right away. You can count on me. It is an honor that I do not deserve, but I will do my best and fulfill my duties well. As for repressing my self-love, we will see later. Now it’s time to accomplish that beautiful task.” A newcomer in the Group would say to us from time to time: “You can be completely worry-free.” I looked at him and thought: Ah, my son, if you knew how worry-free I am, you would be surprised! Could this happen to us? If it can, let us be sure that we are barren like the barren fig tree of the Gospel that does not bear fruit. Because people like that bear no fruit for the apostolate; give it up because it does not have God’s blessing, and no fruit grows from this barren fig tree. At least beat your chest and recognize: “I am a useless person occupying a position with negative results because it should bear fruit and does not by my fault.” At least say that, but do not imagine you are doing good because you are not. Here is the principle enunciated by Saint John of the Cross. |

|