|

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

"Synarchic Morals"

July 1th, 1963 - without author’s revision. |

|

|

One of the most salient aspects of European decadence is a peculiar new morality at variance with the morality of previous centuries, which is being surreptitiously established all over the West. This morality is centered on the idea that production of material goods is the supreme value of every man’s life and society as well. Man is worth something to the degree that he helps to produce and save material goods, whether by action or omission. All, or at any rate, most vices and qualities are worth something to the degree they favor or hinder production. The same can be said of nations. Production of material goods is the supreme finality of man’s life and of every human society. Penetration of this synarchic morality in Brazil is quite visible, above all in the most industrialized centers, as an increase in industrialization, particularly with the aspects it has been assuming lately; for present-day industrialization is no longer that of the time of Getúlio Vargas, aimed only at amassing millions. Today’s industrialist aims, at least remotely, and as a supreme end, to be the manager of a huge organization whose pride and joy is to produce a lot for society and raise the population’s living standards. From the standpoint of personal interest, today’s industrialist, who works enormously, does not quite know why he does it. In order to satisfy greater numbers, he always lowers the quality level. He aims only at producing quantity, with as least quality as possible. The formula to present and promote products is: “They are pretty good” ["bonzinhos", in portoghese]. This is industrialization of the highly industrialized satellite cities type of São Paulo.

Paris, January 2015 In Europe, this spirit can be seen in the contrast between ancient monuments that show the splendor of Europe’s past and today’s European lifestyle. Streets and squares are full of grand things from the past – castles, bridges, portals etc. but the people who live among those splendors are more and more of the ‘modern car’ level: they like to live a modern, good little life. Europeans with some class are still attached to the qualities of products made according to the good old tradition. But every new or modern product is no longer intended to have the same quality as those in the past. That which is old, is at best able to survive for a while, but in one way or another tends to decay. And every new product is always in the “vira-lata” line, cheap stuff tending to shoddiness and vulgarity. This beckons a tendency to generalize an order of production totally different from the old one. And the Europeans of this type, mainly the French, are entirely monopolized by social production. Their spirit, mentality and way of being are marked with the idea of economizing as much as possible. For them, productivity has also become a supreme value. It is the “pretty good” on a European level. Man, a mere producer of useful material goods Now, why call this “synarchic morality”? In current parlance among circles of the European right, ‘synarchy’ is a clan of international tycoons to whom they attribute this state of mind: They do not want to arrive all the way to communism but are filled with the spirit of the Revolution. They are conservatives in the worst sense of the word, wanting to correct nothing and destroy nothing. To combat communism, they are ready to spend any amount, but they are clearly opposed to any return to the past. They couldn’t care less about the slow evolution of society toward the left as long as it does not end up in communism. Their action results in a slow form of Revolution seemingly placed in conflict with the quick form of Revolution which is communism. Although these people appear to be against communism, in the final analysis they favor the Revolution on a very broad spectrum, even more so than the communists themselves. In regions where communism would produce crystallizations, and only in those regions, synarchy deviates reactions. At the same time, it leads those regions to socialism in the way I have just expounded: a lifestyle dominated by the shallow and cheap quality of “pretty good” products and the mystique of work and production. That socialism can be State socialism or socialism of gigantic private companies managed less by owners than by corporate managers with an ever greater tendency toward proletarianization. Thus, through these two forms of socialism, that of the State and that of large companies, theoretically distinct but which live well together in practice, as the latter paves the way for the former, society gradually slides toward communism. It is a slow, rosy, stealth, non-violent and unperceived bolshevization. To move their plans forward, synarchic capitalists produce, promote and encourage in every possible way that synarchic morality centered on the production of economic value and viewing man as a mere producer of material goods. But they do not consider just any production worthy of applause but only that of goods useful for man’s material development. They have no warm applause for merely cultural industries. Characteristics of synarchic morality Synarchic morality has the following characteristics: 1) It is egalitarian; 2) It is depersonalizing; 3) It is materialist; 4) It erects economic production as the criterion of morals. Before examining each of these characteristics, let us study how this morals advances. From the Encyclopedia until 1939 there were unequal [social] classes and an immense ideological struggle through which the Revolution advanced and gradually leveled those classes. People had convictions and adopted ways of seeing things that showed some regard for logic even among adepts of wrong ideas, a regard inherent to the old and good traditions of Christian civilization. Sophistic revolution was necessary to overcome the tendencies being manifested and gaining ground in the order of ideas. The tendentious revolution – for example, Romanticism, the sentimentalism that preceded Romanticism and the French Revolution – was gradually born from the decline of logic and, for its part, accentuated that decline. Along with reason, sentiments began to be clearly manifested in the struggle between the Revolution and the Counter-Revolution. An ideological element subsisted in the Revolution, along with an ever more influential tendentious element. The sophistic revolution was losing ground. In our days that phenomenon became more accentuated, helped by the “new-generationism.” In fact, the “new-generationism” was already beginning in the generations that preceded today’s “new generation” people. Whence the sly and creeping increase in bad tendencies. In the absence of firm convictions, instead of discussing them it was better to slowly occupy the mental space of persons and masses with new convictions. The process of surreptitious entry This new phase enters without attacking the past but by replacing old themes with new ones. But this entry process is surreptitious. Men even continue to be friends of order, hierarchy etc. but this attitude becomes more and more platonic. The sophistic revolution lasted throughout the French Revolution but reached its apex during the 19th century. However, in the last two decades of that century, given the climate of pacifism that was established, the sophistic revolution began to diminish. The need to argue is replaced with an ever greater tendency to remain silent; and the need to dialectically attack or defend the truth disappears. The taste for arguing loses momentum through many decades to arrive at its present situation of near-death. Panic of arguing is one of the traits that characterize today’s Catholic circles. They are afraid, scared to death of internal and external arguments. We have been analyzing the characteristics of the malicious advance of the synarchic revolution. We now must describe how are, in the mentality of today’s man, the relationships between the old doctrines that still linger on and the mentality of the new synarchic morality we are dealing with. The values of former centuries remain alive today. They have lost some of their vivacity but it would be exaggerated to say they have died. So, one could object that we are exaggerating the importance of synarchic morality. But the affirmation I am making should be understood in light of the metaphor employed in Revolution and Counter-Revolution about a tree or vine that wraps around other trees (like poison ivy) and eventually devours them. Evolution of the ideal human model over the last few centuries The ideal man in the Middle Ages was the saint. In the 18th century, it was the viveur; in the 19th century, the brilliant bourgeois; and in the 20th century, the productive bourgeois. The ideal man, in the 18th century, was no longer a saint as in the Middle Ages but a man whose splendor consisted in making life a source of pleasure for soul and body: An elegant, refined and noble source of pleasure, at least outwardly, if not in its moral content. He is the viveur man, that is, one who loves life for the aristocratic and elegant pleasure of living that preceded the French Revolution. In the 19th century, with the advent of the bourgeoisie that ideal suffered some modifications. The great man of society was now the brilliant bourgeois, above all if he was a professional or an artist. To be a great doctor, lawyer, scientist, journalist, politician, or artist was the ideal of a man who was respected and well regarded. When a very rich person favored the arts, that alone gave him some political influence, and so he would intervene in the play of ideas, discussions and intellectual life, and also was respectable on that account. But the 19th century, which saw so many nouveaux riches, also profoundly despised them. The nouveau riche He was the stuff of satire, mocking songs, the very image of a despised egotist. So one cannot say that the rich man was the ideal of the 19th century. As we enter the 20th century, with industrialization, the progress of natural sciences and technology, international trade, the accumulation of large fortunes, prestige now increasingly surrounds economic production. To amass large fortunes has become something prestigious. It matters little if the person is ill-bred, ridiculous, pretentious, or that he has made a fortune in a prosaic or even dishonest fashion: he is rich. With the ever greater drop in moral and intellectual values and the cynicism and opportunism becoming more and more accentuated with the general decadence of morals, there is greater understanding toward the parvenu [he who has ‘arrived’] and even some regard for him. This admiration, which existed in Europe in some way, was immense in the United States. The self-made man, king of canned onions or chewing gum, who has some patent that earns him an incredible fortune, is a type admired and venerated by men in the beginning of the 20th century and throughout the period that ends roughly at the beginning of World War II. This parvenu, who is far from being the aristocratic man of old [hidalgo], tries to appear like one as much as possible. He buys a title of nobility, marries in the aristocracy and builds palaces resembling wedding cakes. He tries to imitate the refinements of ancient nobility with stupid means such as bathing in champagne. Postwar misery generates synarchic mentality Only later, with the advent of postwar misery – for the World War brought misery so that the pre-existing horror of misery, pain and any form of suffering became much more accentuated and gradually gave rise to another personage as the ideal social type. Phobia of misery brought an obsessive desire to satiate everybody’s hunger and produce as much as possible and as cheap as possible to attain that end. The idea of individual profit was replaced with that of collective service. And the synarchic type of which we have spoken appears. What relationship is there among these things? The tree of the 18th century, which would be admiration for an elegant and noble man, was not entirely destroyed by the tree of the 19th century, which is admiration for the brilliant bourgeois. On the contrary, the brilliant bourgeois sought in many ways to be like the noble, imitating his spiritual values, culture, knowledge and manners as much as possible. And throughout the 20th century, nobility, though in a state of decadence, continued to exercise an influence which, under some aspects, was preponderant. For if they were no longer the dominant class, the nobles served as ideal and model for the dominant class. But the play of forces between the bourgeois class and the aristocracy was such that, as the two lived together, the bourgeois mentality acted like a poison ivy that sucks the life out of the tree. In the bourgeois world, aristocratic values existed like an old tree, rotten wood being devoured and killed by new, living wood. Each day marked a set back for the nobility and an advance of bourgeoisism. After the intellectual bourgeois came a bourgeois whose grandeur was calculated according to matter: the nouveau riche. This no longer imitates the nobleman in his spiritual values but in his material opulence. He is like a poison ivy that eats up that tree. After him there finally comes the productivist bourgeois who no longer has any form of grandeur except for the collectivist grandeur of production. He no longer imitates the nobleman in absolutely anything. He is another poison ivy that, for its part, devours the bourgeoisism of the parvenu millionaire. As one can see, the most recent dynamic force that increasingly eats up the others is this new synarchic bourgeoisism. But there still is in public opinion, in a state of decay, admiration for the nouveau riche; and in state of even greater decay, regard for the intellectual bourgeois, the university professor etc.; and in even greater state of decay, regard for the nobleman. None of these regards has died entirely, but each of these trees, even before having eaten the former, begins by being eaten by another one that succeeds it. This explains how these various admirations can continue to exist, but in a state of agony. Admiration for the nobleman has been almost annihilated, while admiration for the intellectual bourgeois still has a bit more life to it. But the nobleman can tell the bourgeois: “I was what you are, and you will be what I am.” The bourgeois can tell the nouveau riche the same thing, and the latter can say it to the boss of the synarchic era. New ideal: union leader in a proletarian society Synarchism did not eliminate those values entirely but increasingly withdrew life and sap from them. Today, only synarchism truly has life. But one can already have a glimpse of what the new important man of tomorrow will be: a union leader in a totally proletarian society. For now we are in the era of the prestige of production. Imagine an important industrialist who is at the headquarters of the Federation of Industries conversing with friends before a meeting. A friend asks him, “What do your children do?” Let us suppose he had to answer: “They do not work because I am rich, so they enjoy life.” Today a man would not dare give such an answer, which would be seen as more or less normal one hundred years ago. He would not dare to say he has completely unproductive children. He would feel a little less shameful if he could say that since his children did not get accustomed to the Brazilian ambience, they went to live in Europe. There, one does not know how (for he will say he had nothing to do with that) they get along well with aristocratic ambiences and are well accepted, so they live there. One is engaged to marry the daughter of prince so and so, and the other the daughter of duke so and so. He would say that with some embarrassment. But since here you still have the acquisition of some value, though archaic, anachronistic and execrable, he says it with less shame than when he simply affirms that his son does not work and lives exclusively from interest. But here still he does not say that with much satisfaction. This is so true, that if he had a son who was a great university professor he would comment his situation in a different way. He would say he followed a different path by plunging into research and living for science; that no one has any idea how hard he works; that he received international awards etc. This is already more beautiful, comparing to the noble. Idolizing the synarchic mentality Clearly, that industrialist would like even more to be able to say that his third or fourth son is a hard-working market investor who works from dusk to dawn and is doing very well and accumulating a very reasonable personal fortune. But this is not as beautiful as production, as he is profiting from playing the market. In some circles it would be better to say that his son is doing well, having started from scratch without any help from his father at all. He would not even start working in his father’s company and went to some other firm. There he advanced so much that he was promoted and later moved to his father’s company, where he is now the manager. He works very hard, in fact he is perhaps the one who works the hardest in the whole factory. He is the first one in, the last one out, has no privileges of any kind; he is a very simple person, friendly with all co-workers, frequents the employees’ club and so on. Since it would be a little bit too much to go that far in the way of proletarianization, the father adds that his son is now engaged to so and so, a chic lady. But he is the son who makes his father proudest, since he is the one who produces more. The father is proud of his son to the degree that his activity is closer to economic production, reputed ideal, and to the degree that economic production is community-oriented rather than individual profit-oriented. Let us imagine it the other way around, if someone asked a father how his sons were doing and he began with this latter son, very proudly. When he spoke of the one who plays the market, he would do so with less enthusiasm; and with even less enthusiasm, of the university professor. Of the aristocrat he would speak clearly embarrassed. And he would be shameful to no end when speaking about his “useless” son. Through these two degrees I believe I have made clear how the other values are moribund. Almost all of them can be called values only in a very relative fashion, because in part they cause shame. On the contrary, production is the only authentic value that exists, the one that gives only pride and no shame. Exemplifying with daughters To put it in more emphatic terms, let us imagine he had daughters. In Brazilian society, the idea that women must also be a factor in economic production is still not acclimated. If a father answers that his daughter is ideal because she does not leave home, knits and gets on with her life, the interlocutor will react with an indifferent "ah!," deep inside finding the girl stupid and homely. If he says she spends her life entertaining herself, the interlocutor will think: she is useless. If the father says she is in Europe, frequents high society there, gets along in that ambience very well and is engaged to marry prince so and so, that will be well received, as for a woman that still looks good. Nobility – the same value which is ugly for a man because it distances him from production, is still beautiful on a woman, still not required to be economically productive: she did not stay home drawling, at least she did something. If he says she married prince so and so whom she met while studying at the Sorbonne, he will cause admiration: in addition to marrying a prince, she studied comparative literature at the Sorbonne! But their jaws would drop in admiration if he were to tell them that she stayed at home helping her father in his business and everything is going great; that she is engaged to a young man who’s an employee of her father but who’s making a career; the two of them live to work but love each other dearly. They will be seen like a couple of enchanting doves, as the story serves devoutly the idol of the day: production. There still is greater tolerance toward female unproductiveness, but even women are now judged on their greater or lesser closeness to that ideal point, which is the capacity for economic production. Humanitarian mystic behind synarchic morals As always, this wrong morality is based on a unilateral mystique. On what mystique is this morality concretely based? The mystique is this: There are people who suffer hunger, lack of medicine, have an indigent and uncomfortable life, all the limitations of illiteracy, are subject to the risk of accident and wearing out at the work place, suffer the hardship of having superiors and being obliged to obey orders. These cases are countless: perhaps most of mankind finds itself in that situation. But even if such cases were not countless, they still are strictly unbearable and mankind has an absolute obligation to make that cease as soon as possible. That is such an imperious obligation that everything else must be sacrificed to it. Any luxuriousness is theft because it takes away what those indigent people need. From this comes a uniform tendency to lower the level of all forms of production across the board and produce only what is essential to bring an end to that state of misery among men. At a first glance, this mystique is humanitarian. It is based on the utopia that one can bring an end to all misfortunes. It is based on the premise that pain or physical privation is the greatest suffering man can have. Curiously, this productivistic mentality ignores moral and spiritual sufferings and considers only material needs, thus fitting the Scripture’s description of those whose god is their own belly. It also believes material suffering is strictly unbearable and revolting. It is necessary to make it cease by getting rid of all forms of luxury, pleasure, refinement, etc. Behind the humanitarian mystic, egalitarianism Behind this humanitarian idea, which is eminently secular and devoid of the meaning of the cross and spirituality, another mystique appears: egalitarianism. It is insinuated that man causes suffering to others in that they desire to possess what he has. A perfect humanitarianism would bring about complete equality. Equality is necessary as long as everyone’s hunger is not eliminated; but even if all material privations were to cease, inequality would be irritating and uncharitable. Thus complete equality appears not as a momentary need to eliminate hunger but as the normal and desirable order of mankind. This position can be called Christian in the blasphemous sense in which the sons of the Revolution understand and exploit Christian Democracy; it is a sugar-coated Christianity that loathes the Cross; one whose charity is to hate every type of suffering and merely consider material suffering. One would say that to act the way I have described is very Christian, that it corresponds to the social function of property: First, to eliminate misery, and second to establish equality. I believe this radically egalitarian trait is essential to the state of mind that constitutes revolutionary “Christian” democracy, particularly in our days. Let us see what the role of production is in all this. If everyone produces the indispensable for everybody in large quantities, no one will suffer misery. The ideal is for everyone to have just enough so that no one else will be in need. That is what work is for. There’s no liking or disliking it, it is a duty. It is an activity that must be accomplished. Of course, if factories, machinery and manpower are deviated to found and maintain luxury industries, those resources will be denied the industries that produce the indispensable for man’s sustenance. For this reason, industries that cater to luxuriousness and pleasure must be eliminated. On the other hand, enjoying refinements and luxuries takes away man’s disposition to work. This, in the eyes of the modern synarchic worker, is a soft and suspicious state of soul. Those refinements complicate life. Everyone sees poets, artists and musicians as complicated people, almost as complicated as aristocrats. Why, this new humanity that stays away from those arcane spheres and worries only about producing is so much more likable! One must do away with refinements and complications so that everyone can work, be simple and content himself with little so that the great economic mass can function well and satisfy everyone by with uniform progress. Men have to change their way of being. They cannot be stable, solemn, or thinkers but have to be rapid, agile, superficial and very hard working to produce a lot, for thinking a lot does not fill anyone’s belly. So we have seen the links between egalitarianism, the mystique of work and that of synarchic production, and how synarchic work or productivism end up being the same thing as egalitarianism. The utopian character of the synarchic-productivist mentality Clearly, this influence produces a whole social ambience that we will analyze soon. Before moving ahead, I insist on the utopian character of this state of mind: “One must be optimistic. Nothing will become complicated or messed up; everything will work out all right. There is no point crying. The norm is, ‘break your leg but keep smiling.’” This causes little commotion in the parents of an accident victim and it is good because they can go to work without worries and without getting the doctor annoyed or concerned. What is the point moaning if the doctor already knows how much a broken leg hurts? A non-annoyed doctor cares for two patients; if you smile you help fix your leg and that of the other person too. So, a sense of ‘social justice’ leads you to keep smiling when you break your leg. Certainly, one day technology will end all these pains. One must look at the future of the world with optimism. With an optimistic state of mind, man can even feel less pain through the power of self-suggestion; pain is a kind of fantasy and belly-crying from the past. The proof is that women are now able to have children without pain, through a form of hypnotism and a play of elbows. And if science was unable to prevent men from slipping and breaking their leg, at least a day will come when man will have a way to avoid feeling pain when he breaks his leg. He will be waiting on the sidewalk with a bottle of coke to kill time until he can be taken to hospital. As a technique that highly simplifies the human soul, bureaucracy will eliminate all real or imaginary pains. So, let us be optimistic, joyful and smiling. Obviously all this contains a huge lie, an immense utopia, but one needs to believe it in order not to become a marginalized party spoiler, as only that type of optimistic and smiling man is likable.

The Hospices de Beaune or Hôtel-Dieu de Beaune is a former charitable almshouse in Beaune, France. It was founded in 1443 by Nicolas Rolin, chancellor of Burgundy, as a hospital for the poor. The original hospital building, the Hôtel-Dieu, one of the finest examples of French fifteenth-century architecture, is now a museum. Bellow, the Room of the Poor. This is an exemle of the oposite synarchic mentality

Repercussion of this mentality in medicine and hospitals The repercussions of this kind of attitude in medicine are enormous. For example, relatives must not stay with the patient. The doctor and technology will take care of him; a relative means compassion, company, mercy, soul. Now then, for this productivistic world there is no soul. A man who broke his leg has no pain in his soul but in his leg. Therefore, there is no use for any relative to be near him, as it will not fix his broken bone, and that’s what his problem is. Stay alone, smile always and don’t bother the nurses so they can take care of other patients and respect their schedules and union rules, for they too have a right to not suffer. You must carry yourself so as not to weigh on others. Is it not enough that you are not working and thus diminishing production by lying immobile in bed? Out with relatives! Let the patient be left alone and without a bell to ring, for can be severely upbraided if he rings the bell for no reason. And just take that and smile. Only in this way the productivist hospital will move forward. Obviously, euthanasia goes very much along this line. To eliminate children born with a physical defect or elderly people who no longer want to live, or those who are believed they should no longer want to be living, such as the terminally ill and so on. Weight-loss diets also have to do with this. Never has medicine discovered so many inconveniences to being fact. In fact, the worst part of being fat is that the fat man carries with him many proteins that should belong to someone else. He is a kind of shark who monopolizes fat while some emaciated man in Malaysia could live well with that fat. The fat man is an egoist, and as such he should be disliked. So medicine recommends thinness. How could we describe a human type formed according to this mentality? Let us describe a man and a woman. Since all inequalities get in the way of production (because the more standardization, the more production), the man-type and the woman-type must be as similar or as little different as possible. But some difference still subsists, as the weight of tradition is great. I must say that synarchic morality is very feministic as it wants to masculinize women. It is also somewhat masculinistic in the sense of seeking to effeminate men so as to establish a median quid. But it is above all infantilistic. It wants to turn men and women into idiotic and soulless beings – big giddy funny kids with all the defects of a child’s lack of reflection and spontaneity, almost like the mentally retarded. During childhood, the sexes are less differentiated. By leading men back to their childhood, synarchy obtains a maximum lack of reflection, physical agility and dynamism for work and for leveling everything and everyone. So, reducing everyone to a state of physical adolescence and intellectual childhood is the ideal to which synarchism leads. Synarchic morality exemplified in a couple Since we are analyzing a man and a woman, let us consider a couple with small children (this is the apex of synarchic matrimonial life, when everyone is young and all is well). In very rich families, what characterizes this couple is the fact they never become proletarian and never move to a different social class. But inside their own class, they are as proletarian as possible without dropping down to the next class. Let us imagine, for example, an extremely rich couple. They may have a large house. But in their large house, practical concerns are much greater than aesthetic ones. In old times the concern was to furnish the house in a beautiful and even sumptuous way. Kitchen, pantry, maids’ quarters, cupboard etc. were all equipped in a sufficient way. Not so today. A young housewife’s pride is to have a super-washable kitchen organized with a practical mind, in which everything works as well as if it were a factory. The laundry and ironing rooms are in the same style; the maids’ quarters are stupendous. There are well-ventilated storage rooms to prevent foodstuffs from spoiling, with neon lights, easy to clean etc. All this is the pride and joy of a synarchic housewife who gladly saves on something superfluous for the living room to be able to have the maids’ kitchen or bathroom in the best possible shape. In this sumptuous household there is a budget for cars as needed, but no concern for having a beautiful, representative vehicle. If they buy a very expensive vehicle, it will be a beautiful van, but something with functional utility to transport chickens, vegetables and children from or to the farm or the sea, excursions in the countryside etc. The ideal is to have two or three small cars, easy to drive, which both the housewife and her governess drive. If needed, any of the two can to go the market and run errands. Maids can be hired as needed, but it is better to have as few as possible. The greatest mania is about cleanliness. A maid can work her heart out, but everything must be spic and span. This is understandable. That which is not clean but dirty brings with it an image of death and evil. This contrasts with the utopian spirit that dominates that mentality. That spirit also exists somehow in poor and middle class households. Let us suppose a house of the small or medium bourgeoisie. Everything is clean, washable, and easily replaceable, everything must be always new. The housewife, having one or two maids, also cleans a few things; the difference between the lady of the house and the maid is not so great, nor is that between the father of the family, his driver and other employees. They converse and have a certain friendship. Obviously, the tendency is to suppress the maids; that would be beautiful because it indicates production. A micro-synarchic couple, in a modest house, have as much as possible a mechanized home, an excellent vacuum cleaner, egg-beater, liquefier, refrigerator, television set, and delicious air-conditioning. Funny, people like that have a certain bashfulness about feeling cold and a certain phobia of the heat. To the point that, if they go to the beach, they don’t say they feel hot. They act as if the heat didn’t bother them. To feel hot is something ignominious. In the house of an average couple, everything must be cheap, but it must be cheap with a joyful, sprightly and unpretentious look, as something durable. Nothing would be grave, serious or solemn. A grandmother’s portrait would be shocking in that ambience. The children must be joyful, healthy, play with one another. Their mother cares for them. In regard to children, people with the synarchic labor syndrome can be divided into two tendencies: 1) Malthusian: forget about having many children, as we might run out of food; 2) Productivist, that is, it foments the birth rate: Let there be many children, because each children is a worker. One is a tendency for people with a Protestant taste, the other for people with a Catholic taste. The depersonalizing character of synarchic morality The entertainment of these synarchic people is simple. First of all, they do not have vast social relationships, for that would mean prestige, and prestige means soul. Prestige is a spiritual value, that is, a fiction, a cumbersome pain in the neck. The couple has a small circle of friends with whom they entertain themselves. It is a limited circle in which relationships are very simple, there are no ceremonies, and above all everything takes place in the strictest intimacy. Entertainment is television or a quick, light and insignificant conversation. All these are ready-made commodities. There is an entertainment industry that serves the whole city and all social classes. An automobile is for everybody, as having an automobile is everyone’s ideal. They entertain themselves in waves. It is fashionable to spend the summer in Guarujá beach, so everyone goes. No one needs to think about choosing his entertainment, because it is completely socialized and mass produced for everybody. And everybody has a sufficient level of entertainment. It is not politically correct to praise refined entertainment for small groups. It is only in that socialist atmosphere that people entertain themselves. Work dominates everything so that pleasure ends up by being an image of work. The person no longer entertains himself like a pasha sitting on cushions with a hookah, or as an intellectual or noble sitting in brilliant halls, but rather camping, surfing, climbing a mountain, making excursions of all sorts because that is the image of work. Note that hunting is not much liked, for humanitarians have pity on animals. Sports pleasure is good because it prepares the person to work and does not diminish his productivity. We must admit that work itself also is collective. Men of exceptional intelligence must be cast aside. Teamwork produces well and for everybody on a regular basis, and that is the right way. And universities form scores of cretins, very well informed and endowed with perfect files for this type of work. And that is how synarchic university is: it only provides information, not structures or general concepts. People have piles of file cards and resolve concrete little cases; material life goes on, and all is well. That type of people does not like the horror of modern art. This is because the horrible is the sublime of the ugly, and so it must not be accepted either. Works of art are reduced to big boxes like Brasilia, compressed or stretched. You don’t need an artist to make that, all you need is a team that realizes the functional needs, which are studied and explored by the team and decided by it. In this situation, obviously nobody is anybody, everyone is anonymous. And the only form of prayer that goes with it is liturgism, as people, arriving in church, pray the way they live: in common, as a team. They wouldn’t know how to do anything else. What will be the end result of all this? Clearly, in this dreadful dawn of synarchism these things are only beginning, but they will become more and more accentuated: there will be ever greater egalitarianism, depersonalization and adoration of material values. As this process advances, it must necessarily lead to communism. With the appearance of combating communist morality, synarchy in fact introduces a specific morality which is a preparation for communism. A true Catholic must hate synarchy Let us see what attitude a Catholic must take in the face of this. Just as a true Catholic would not want to be a liberal or a socialist, so also he must hate synarchy. St. Joseph and Our Lady were the opposite of ‘productive’ people and so was Our Lord. St. Francis and St. Clara of Assisi represented exactly the opposite of a corporate businessman who adores production.

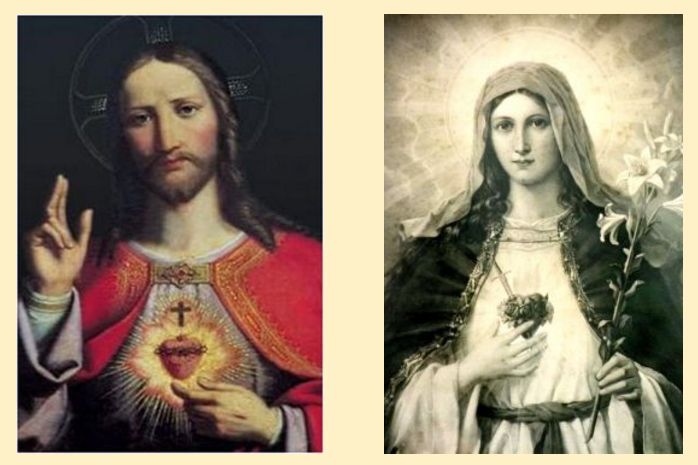

St. Francis and St. Clara of Assisi The good of temporal society is first of all a good of the soul and only then one of the body. And production of intellectual and spiritual values to help with eternal salvation is more necessary for humanity than production of material goods. Of course one must tend to eliminate catastrophes, but not at the cost of preventing people from having culture or soul so they don’t go hungry. That would be imposing an unbearable life on everyone: in order to preserve the lives of some, it would take away everyone’s reason for living. In other words, however hard one tries to resolve the situation of those suffering material needs – and a Catholic must desire that with all the strength of his soul – one cannot reach the point of destroying all elites, all true culture, and all refinement. Synarchism is tantamount to introducing a morality applied only with a negation of the spirit. That morality would be true only if men were nothing but matter. It is the logical consequence of two premises. One is materialism, the negation of the whole Catholic doctrine; and the other is the negation of man’s personality and thereby also a negation of Catholic doctrine. It is the construction of a morality and a new world founded on the error of an exclusively collectivistic piety – liturgism – whereas Catholic formation is essentially and above all personal. For us to be able to fight this error we must combat in our souls the myth of the man who knows, can, does and has. He has already become somewhat anachronistic as a plutocrat, for today he is merely a manager of his assets. He is no longer a salient man and presents himself as equal to everyone, thinking like everyone and being everyone’s level; one who knows as much as anyone, has as much as anyone, and does all that everyone does, ashamed of being less and also of being more. This is the abomination of egalitarianism. Being productive in the moral order When a man is more, he rejoices and sees that as another, more faithful reflection of God. When he has less, he also rejoices, and sees it as an imitation of Our Lord’s voluntary poverty, and gives thanks to God. He is not continually wishing to be equal to everyone. We must preserve ourselves from this synarchic morality with the same care that we must preserve ourselves from all errors. And we must be even more careful about this one, for a living error always has a greater power of seduction than a dead error. We do not run so much the risk of deforming our souls with errors from past centuries but with errors of our century, as unfortunately we are children of our times and feel all the charge of the bad attractions our century has. We must, with extremely special care, trample underfoot the synarchic idea that we need to be equal to everybody else, that we must not want to have beautiful, noble or refined things, and that we must think that the most beautiful thing for man is to be productive in the material order. In fact, as Catholics we should not even think that the most beautiful thing for man is to be productive in the spiritual order, but rather that it is to be productive in the moral order. Productive of the love of God. As his ultimate end, man was made not to produce but to love God. And when he loves God above all things, he has the prize Our Lord Jesus Christ promised: “Seek ye first the kingdom of God and his justice, and all these things shall be added unto you.” And we will have eternal life to boot. Only thus – by completely rejecting the synarchic spirit – will there be an orderly, calm, stable and sufficient material production without the utopia of eliminating all miseries but with a real and earnest commitment to reduce them as much as possible without prejudice to the moral and intellectual needs of a hierarchical society. If that is not the case, charity disappears, leaving only the cold sentiment of social justice. Accompanied with charity, social justice is a beautiful thing, but without charity it is a monster. It is like a human eye unaccompanied by the other. Both were made to be together, but when a person’s face has only one, or the other is thrown to the ground, it conveys the impression of monstrosity. On the other hand, we must understand that even for a poor man – who, we repeat, must be assisted by every means in his material needs – it is a lesser evil to have a society filled with spiritual values and suffer some privation than to have a society empty of spiritual values and a full stomach. Having one soul’s filled is more necessary than having one’s belly filled. In this case, a soul filled with the love of God, the light of the Holy Ghost, of the Roman Catholic and Apostolic Faith, in which we have been raised. From many standpoints, the task of fighting against this synarchic morality is so grave and arduous that it cannot be carried out without divine help. And we must ask for that help through Our Lady, Mediatrix of all grace. We must ask the Sacred Heart of Jesus for it through the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

With the devotion of the Sacred Hearts, the Church emphasizes the opposite of productivist materialism. What the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary teach us about, are problems of the soul, pains of the soul, desires of the soul and the satisfaction that one finds in God. Let us ask these Hearts to give us a meticulous and exact repudiation of all the errors of synarchy and a full conviction and practice of the Catholic truths opposed to synarchic morals. |

|