|

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

How

many saints were noble?

Nobility and Analogous Traditional Elites in the Allocutions of Pius XII: A Theme Illuminating American Social History (*) |

|

|

The current misunderstanding of nobility and the analogous traditional elites results largely from the adroit but biased propaganda spread against them by the French Revolution. Such propaganda, continuously disseminated throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries by ideological and political currents spawned by the French Revolution, has been challenged by serious historiography with growing efficacy. This propaganda, however, still clings to life in certain sectors of opinion. It is relevant, therefore, to say something about this. According to the revolutionaries of 1789, the nobility was essentially constituted of pleasure seekers. Holding honorific and economic privileges, the nobles allegedly lived extravagantly off the merit and credit acquired by distant ancestors. This allowed them the luxury of enjoying earthly life, especially the delights of idleness and voluptuousness. This class of pleasure seekers was also highly burdensome to the nation and harmful to the poorer classes, which were hard-working, temperate, and beneficial to the common good. According to d’Argenson, “La Cour était le tombeau de la nation” (the Court was the nation’s tomb).

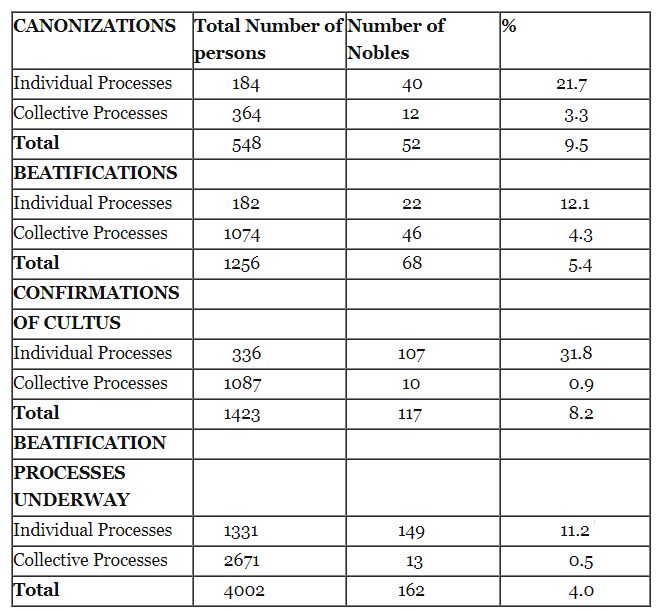

Some of the Noble Saints Canonized between 1198 and 1431; Top, L to R: St. Robert of Molesme, St. Dominic de Guzmán, St. Lawrence O’Toole. Bottom Row: St. Francis of Assisi, St. Elisabeth of Hungary & St. Hugh of Lincoln This led to the notion that the life of a noble, with the station and wealth that normally accompany it, induces a moral negligence that sharply contrasts with Christian asceticism. This perception contains some measure of truth. The first signs of the terrible moral crisis of our day were already visible among the nobility and the analogous elites of the late eighteenth century. It is necessary, however, to stress that this perception is much more false than true and is harmful to the good reputation of the noble class. Many aspects of the Church’s history prove this, including the fact that she has raised a great number of nobles to the honors of the altar. She thus affirms that they followed the Commandments and the evangelical counsels to a heroic degree. Saint Peter Julian Eymard has noted that “the Church annals show that a large number of saints, and the most illustrious ones, had a blazon, a name, an illustrious family; some were even of royal blood” (1). While several of these saints abandoned the world to more securely attain heroic virtue, others, such as the kings Saint Louis of France and Saint Ferdinand of Castile, remained amid the splendor of their lofty noble stations and therein attained heroic virtue. To complete the refutation of this perception, which seeks to degrade the nobility, its customs and lifestyles, we thought it advisable to enquire about the proportion of nobles who were canonized by the Church. A specific study on this subject could not be found. Some investigators have broached the subject without undertaking specific and exhaustive research. They based their calculations on registers that they themselves present as incomplete. University of Rouen professor André Vauchez published a study, La Sainteté en l’Occident aux Dernières Siècles du Moyen Age (2), based on the processes of canonization and on medieval hagiographic documents, that merits particular attention. He analyzes the investigations de vita, miraculis et fama ordered by popes between 1198 and 1431. Of a total of 71 investigations, 35 concluded that the persons examined deserved to be elevated to the honors of the altar, which the Church did in the Middle Ages.(3) The statistics furnished by Vauchez follow: Processes of canonization ordered between 1198 and 1431 (71 cases) Nobles 62.0% Middle Class 15.5% People 8.4% Social origin unknown 14.1%

Saints canonized by Popes of the Middle Ages (35 cases) Nobles 60.0% Middle Class 17.1%

People 8.6% Social origin unknown 14.3%

Even if very interesting, this data does not offer a complete picture, since it relates to a very small number of people and to a relatively short period. An investigation encompassing a larger number of people over a longer period was necessary—not that it would exhaust the subject. Nevertheless, some weighty difficulties arose. First, there is no official list of the saints venerated in the Catholic Church. This is explicable and is related to the very history of the Church and the gradual perfecting of Her institutions. The veneration of saints had its start in the Catholic Church with the homage paid to the martyrs. Local communities honored some of their members who were victims of persecutions. Of the thousands of those who shed their blood in testimony of the Faith in the first centuries of the Church, only a few hundred names have come down to us. We know them through the acts of the Roman tribunals, which transcribed the oral processes, and through reports made by eye-witnesses of the martyrdoms. Many records of the martyrs were simply lacking. Of those that had existed—whose reading inflamed the souls of the first Christians and gave them the strength to bear new tribulations—many were destroyed during the persecutions, especially that of Diocletian.(4) Thus it is impossible to know all the martyrs venerated by the faithful in the first centuries.

Top row, L to R: St. Joan of

Arc, St. Nuno Álvares Pereira, St. Katherine Drexel. Bottom Row: St.

Jadwiga of Poland, St. Norbert of Xanten & St. Ivo of Kermartin (also

called St. Yves). After the persecutions, and for a long time, saints were venerated by restricted groups of faithful without prior investigation and pronouncement of an ecclesiastical authority. As the authority’s participation in the organization of the Catholic communities grew, its role in deciding who should receive veneration also grew. The bishops began to sanction this or that cultus, and often ratified it at the request of the faithful. They even made the exhumation and translation of a new saint’s relics. Only at the end of the first millennium did the popes begin to intervene occasionally in the official recognition of a saint. As the Roman Pontiff’s power was affirmed and the contacts with Rome became more frequent, the bishops began to solicit the pope’s sanction of these cults. This occurred for the first time in 993. Between 993 and 1234 many bishops continued to translate relics and to confirm cults according to the ancient customs. Later, recourse to the Holy See was made compulsory by the 1234 Decretals, and the right of canonization was reserved to the Pontiff. From 1234 on, the processes for determining the veneration of a saint were gradually perfected. From the end of the thirteenth century, the pontifical decisions were based on a prior investigation carried out by a college of three cardinals especially entrusted with this task. This remained the case until 1588, when the causes were confided to the Congregation of Rites, established the previous year by Pope Sixtus V. In the seventeenth century this development reached its term. In 1634, Urban VIII’s brief Coelestis Jerusalem cives established the standards for canonization, which remain essentially the same to our day. The Constitutions of Urban VIII established the confirmation of cult, or equipollent canonization, for those servants of God whose public veneration had been tolerated after the pontificate of Alexander III (1159-1181). An equipollent canonization is a “decision by which the Sovereign Pontiff orders that a servant of God who is found in public venerations from time immemorial be honored in the Universal Church even though a regular process has not been introduced.”(5) This procedure was valid also for similar cases occurring after the Constitutions of Urban VIII. From 993 on (the date of the first papal canonization) it is possible to establish a list of saints designated by the Holy See. This list, however, is still not complete. Documents of extensive periods are missing. Furthermore, the list does not contain all the saints, for between 993 and 1234, as noted, the bishops continued to ratify cultus. For this reason, many individuals were objects of public veneration independently of Rome’s intervention, which was often—but not always—requested only some centuries later. Only with the beginning of the sixteenth century can one be certain that the list of saints and blessed (a distinction established by the legislation of Urban VIII) is complete.(6) Apart from the difficulty in compiling a complete list of the saints, there is the problem of determining who among them belonged to the nobility. The certainty of a person’s noble origin is not always easy to establish. On the one hand, the concept of nobility developed progressively and organically, conditioned by local characteristics. On the other hand, it is sometimes difficult to determine with precision the ancestry of a person, and thus to determine the social origin of a saint. Having these difficulties in mind, we had to choose the most complete and trustworthy sources possible in order to determine the approximate number of nobles among the saints. The Index ac Status Causorum (7) was chosen because it is an “extraordinary and most ample edition” made to commemorate the fourth centennial of the Congregation and “contains all the causes that came before the Congregation from 1588 to 1988, even the rather ancient ones preserved in the Vatican’s Secret Archives.” The work includes several appendices of which three are of special interest to this study. The first contains confirmations of veneration, some names of the blessed that were added, and those that were removed but later included in the catalogue of the saints. This appendix is based on the Index ac Status Causorum written by Father Beaudoin in 1975. The second appendix enumerates only those beatified since the institution of the Sacred Congregation of Rites but still not canonized. Lastly, the third appendix enumerates the saints whose causes were considered by the Sacred Congregation of Rites, including the cases of equipollent canonization.

St Elizabeth Ann Seton, the 5th American Saint. With this list of names in hand, we consulted the respective biographies in the Bibliotheca Sanctorum (8) to discover which saints were nobles. This work, supervised by Pietro Cardinal Palazzini, former prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints, is considered the most complete catalogue of persons who have received veneration since the beginning of the Church. The Bibliotheca Sanctorum does not focus its principal attention on the social origin of the listed persons, but rather on the problems related to their veneration. Thus, it is frequently impossible to know who was noble. To follow a strict criterion, we counted as nobles only those whom the work identifies as nobles or descendants thereof. Those whom the text merely depicts as belonging to “important,” “known,” “old,” “powerful,” or similarly-designated families were not included. In order to avoid doubtful cases, we further excluded persons who noble origin could reasonably be presumed or even established with certainty through sources other than the Bibliotheca Sanctorum. For yet greater precision, it also seemed convenient to distinguish the following categories, in accord with the Index ac Status Causorum: * Saints canonized after a regular process; * Those beatified after a regular process; * Those whose venerability was confirmed; * Servants of God whose processes of beatification are under way. In the percentages presented in the table which follows, care was taken to discriminate, in each category, between those who were the object of an individual investigation and those who were part of a group, such as, for example, the Japanese, English, and Vietnamese martyrs.(9) To correctly asses the appreciable percentage of nobles in these various categories, we must consider the percentage of nobles in relation to their respective country’s population. We limit ourselves to two quite diverse and significant examples. According the renowned Austrian historian J. B. Weiss, who drew on Taine’s data, the nobility in France before the French Revolution comprised less than 1.5% of the population.(10) In his treatise on universal geography, La Terra,(11) G. Marinelli furnishes statistics on the nobility in Russia, basing himself on the work of Peschel-Krümel, Das Russische Reich (Leipzig, 1880). According to Marinelli, the sum of the hereditary nobility and personal nobility did not exceed 1.15% of the population. He also states that Rèclus, in 1879, and van Lëhen, in 1881, presented similar statistics, both arriving at the figure of 1.3%. Obviously these percentages varied slightly depending on time and place, but the variations are not significant.

The data presented above shows that in each of the categories (canonizations, beatifications, confirmations of cultus, and beatification processes underway) the percentage of nobles is considerably greater than in the total population of the country.(12) This contradicts the revolutionary calumnies about the supposed incompatibility between practicing virtue and being and living as a noble. Footnotes: (1) Mois de Saint Joseph, p. 62. (2) André Vauchez, La Sainteté en l’Occident aux Derniers Siècles du Moyen Age (Rome: Ecole Française de Rome, Palais Farnese, 1981), 765 pp. (3) Several others were canonized later. (4) Cf. Daniel Ruiz Bueno, Actas de los Martires (Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, 1951). (5) T. Ortolan, “Canonisation,” in Dictionnaire de Théologie Catholique (Paris: Letouzey et Ané, 1923), Vol. 2, part 2, col. 1636. (6) Cf. André Vauchez, La Sainteté en l’Occident; John F. Broderick, S.J., “A Census of the Saints (993-1955),” The American Ecclesiastical Review, August 1956; Pierre Delooz, Sociologie et Canonisations (La Haye: Martinus Nijhoff, 1969); Ruiz Bueno, Actas de los Martires; Archives de Sociologie des Religions, published by the Group of Sociology of the Religions (Paris: Editions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, January-June 1962). (7) Città del Vaticano: Congregatio pro Causis Sanctorum, 1988, 556 pp. (8) John XIII Institute of the Pontifical Lateran University, 12 vols., 1960-1970; Appendix, 1987. (9) The Index ac Status Causarum does not have the precise number of persons considered in some of these group processes, thus making it impossible to give an exact number. Our figures are, therefore, approximate. (10) Weiss, Historia Universal, Vol. 15, p. 212. (11) G. Marinelli, La Terra—Trattato popolare di Geografia Universale (Milan: Casa Editrice Francesco Vallardi), 7 vols. (12) We notice, in the several categories, an appreciable difference between the percentage of nobles in the individual processes of beatification and in the collective processes. This can be explained by two main reasons. In many cases, the Biblioteca Sanctorum only mentions the names without furnishing the biographical data that would permit one to know if they were nobles or not. Also, most of the collective processes refer to groups of martyrs. Persecutions are usually directed against the whole Catholic population, regardless of social class. Thus, it is to be expected that among the martyrs the proportion of nobles would be similar to that within the population. (*) Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, Nobility and Analogous Traditional Elites in the Allocutions of Pius XII: A Theme Illuminating American Social History (York, Penn.: The American Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family, and Property, 1993), Documents XII, pp. 519-523. |

|