|

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

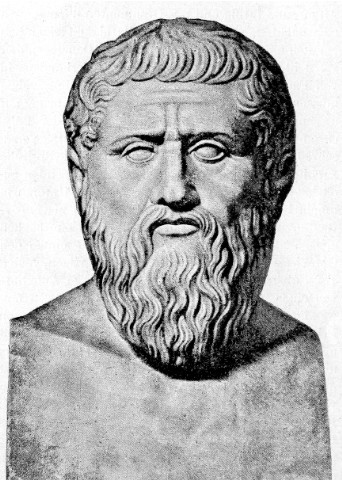

Plato in the union

Folha de S. Paulo, 26th March 1983 |

|

|

The mediocre man has some notions about many things; I mean vague and fluctuating notions which demand no effort to acquire or preserve. Whenever he wants to express his notions, he thinks he attains utter fulfillment by finding a showy word, or at least one that is not part of trivial speech. In our milieu, the term "radical" is one of the mediocre man's favorite words. He senses that branding a foe a radical will be harmful to him. To be "radical" provokes a meticulous and exacerbated rejection. So, it is a good thing to be antiradical because it wins one much support. Thus, we can see our mediocre man quixotically displaying antiradicalism wherever he goes. But as soon as someone contends that such a fiery antiradicalism is nothing but another form of radicalism, he will shrink and change the subject, because in order to refute that objection — so obviously true by the way — the mediocre man would have to know in depth the exact meaning of the word "radical". Now, his idle spirit abhors precise and profound concepts. Analogous to this is the mediocre man's use of the word "liberty". It reminds him right away of the hackneyed trilogy he likes (and of which he has already heard a thousand eulogies): "Liberty, equality, fraternity." Besides, liberty calls to mind the striking statue in the harbor of New York City, which he has seen in pictures and ads; and also a vast and densely populated neighborhood of the city of São Paulo, Brazil. In his youth he used to smoke Liberty cigarettes. And he has in his mind the general idea of liberty as something that provides everyone with the possibility of doing absolutely anything he finds delightful. When he was a child, this word found its way into his mind. His teacher used to keep undisciplined students after school and have them copy endlessly sentences like "A good boy is obedient and studious." When time was up, the teacher would happily exclaim: "Liberty, liberty!" And all the brats would dart out into the street eager for foolishness and rowdiness. This was the ideological core that the word liberty left in his mind. In one way or another, the cigarette, the monument and the neighborhood celebrated that delightful thing called liberty. The trilogy seems to suggest to him the same thought the teacher had in mind when the word blossomed from his smiling lips. The mediocre man has no idea that his superficiality can have profound effects. If someone were to tell him so, he would laugh in disbelief. It would be an easy task for anyone to face a mediocre man. It is less easy to face hundreds or thousands of them. This, however, is the inevitable contingency awaiting whoever publishes today, because the mediocre fill the earth. I do not believe the mediocre will be the greater part of those who will read these lines about them. It is understandable that they will not find them pleasant. But a glance at one or another topic of this article will be sufficient to infuriate many, because every man — even the mediocre one — is sharp and perspicacious when he is spoken of. Nevertheless, I do not hesitate to declare, even before the mediocre ones, the noxiousness, the profound noxiousness of their frivolity. Being persuaded that liberty is good, the mediocre one concludes that the more liberty there is, the better. For him, absolute liberty is total happiness. As a voter, the mediocre one will cast his ballot for the candidate who will promise him unrestricted liberty. As a candidate, the mediocre one draws the support of all of his ilk. Whence he transforms his electoral campaign into a foretaste of absolute, total and unbridled liberty. This naturally brings about, for all slates, the listing and the victory of a varying though sizable percentage of mediocre ones. Hence, the diffuse impetus of legislation and government towards the foolish, the offensive and the gross. Because, when anything goes, then... That impetus also spreads from the sphere of the state to all other sectors of society. Is all this no more than the very well known picture of today's reality? — Let the reader examine the following text: "When a people is devoured by the thirst for liberty, it will have leaders who are ready to minister to this craving as much as the people wish, to the point of inebriation. "If rulers then resist their subjects' ever more demanding desires, they will be called tyrants. "It also happens that he who is orderly under his superiors is singled out as a servile man without backbone. "And that fathers, in dismay, end up treating their sons as their equals and are no longer respected by them. "Masters dare no longer reprove their pupils, who laugh at them. "The youth will claim the same rights and consideration given to their elders and the elders will say the youths are right, so as not to seem too severe. "In this atmosphere of liberty there is no consideration or respect for anyone, for liberty's sake. "Amidst so much license there springs up and develops an evil plant: tyranny." Is this a picture of present day reality? — Certainly, the picture describes very well the stormy days we are living in. And with genial subtlety and precision it points out how the sowers of tyranny — the communists nowadays — profit from the typhoon of demo-mediocrity. But this picture originated... long ago: in the Fourth Century before Christ. Its author is Plato, who so denounces the radicals of liberalism in a democracy, as the true fathers of dictatorship. The passage is taken from The Republic. It fits not only the Fourth Century before Christ or today. It is perennial. It is in the very nature of things. And I have something else to add: I did not transcribe it directly from the great philosopher's work. I limited myself to verifying that those words are truly his. They are simply extracted from the original by way of condensation (cfr. "The Dialogues of Plato," Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., Chicago, London, Toronto, 1952, p.412). A friend of mine found it framed and hung on a wall of... a union headquarters. Thus did the great and solemn Plato penetrate into a union. Not a union of rich employers, nor of scholarly professors; but rather one of... taxi drivers in Rome! Such a fruit is not born of demagogy, but of a people's culture and tradition. And I emphasize the word "tradition". |

|