|

Chapter 2

The Family at the Origin of Feudalism

|

|

|

The family is an institution of the natural order, founded on a sacrament, and given the task of perpetuating the human species and educating the offspring. "Conversion of Clovis", Orsay Museum, Paris When the Roman Empire was at its apogee of earthly splendour and glory, when it was renowned for its administrative and judicial institutions, its cities were linked by roads that are an engineering feat, some of which still survive. These roads permitted troops to defend the Empire’s borders and to keep the provinces under submission. They also facilitated travel by foot, horse, or oxen cart—a rather more common occurrence than we might suppose. The oxcart was the luxury mode of transport of the time: a convoy of up to ten carts provided all sorts of amenities for their travellers, even snow with which to make ice cream. This situation drastically changed when the first barbarian hordes overran the Empire. The Franks were the roughest barbarians one could imagine, but as time went by they became a bit more civilised—though precariously. By the 7th and 8th centuries the hordes were just short of fullfledged barbarianism—the very modest fruit obtained by the Catholic Church after a tremendous struggle. She had pried some from Arianism, converted others, and gradually smoothed the rough edges off their customs. Then, in a tragic fashion, the hurricanes of adversity blew in earnest upon this immense but fledgling work. The floodgates of the non-Christian world opened up and waves of pagans invaded Europe. From Russia and Prussia—regions still unknown at the time—descended barbarians even more primitive than those of the first invasion, laying waste, sacking, and reproducing the horrors perpetrated earlier in the Roman Empire of the West. The Vikings, just as rough, came by sea from the north. At a certain moment, taken up with a sailing frenzy, families, tribes, nations, the whole kingdom set sail. They would travel in their longboats along the coast sacking, devouring, and levelling everything. Some of their chiefs called themselves “Sea Kings”. In this way they reached as far as Constantinople and invaded Byzantium. They always razed everything in their path and at times made profound incursions inland, leaving behind a few men who would continue the work of destruction. From the south came the Saracens. Crossing the Mediterranean into Spain, some invaded all the way into the heart of France, while others invaded Italy. All the forces of hell were unleashed upon Western Christendom. It was an immense disaster. A civilisation whose edifice was just rising from the ground and that had been born from a miracle—the miraculous conversions of the Arians and Franks—was subjected to a hurricane that tore apart everything. Indeed horrified with what was happening, the more civilised men began to climb hills and mountains and to establish themselves on less accessible spots so that when the invaders came their destructive force would be impeded by natural barriers. At the same time, they also began to sow and harvest and build houses behind swamps and places called marécage, or marshes, behind which are found fertile lands. The barbarians, who roamed the main roads between large cities, would not be able to find them hiding behind marshes, on mountains, or in more inhospitable regions. These were disorderly flights of a terrified people. It was not whole cities that took flight, but groups of families; everyone went where one could. In face of the harshness of both nature and adversaries, and no longer having a State to govern them—as the weak and powerless kings could no longer make their orders reach those absolutely inaccessible places—they were reduced to the initial basic cell of society: the family. This primary natural organisation enabled them to survive. From this basic group emerged the paterfamilias, which was at the same time a political, economical, and religious unit constituting a small country in each locality. In each of these social groups, a man usually endowed with greater talents would assume leadership. He was the natural support of that fugitive community. A man with a very broad personality, endowed with a talent to lead, with an understanding of the surrounding dangers and a capacity to organise. Everyone felt supported by him. He organised life and his offspring inherited his qualities and functions.

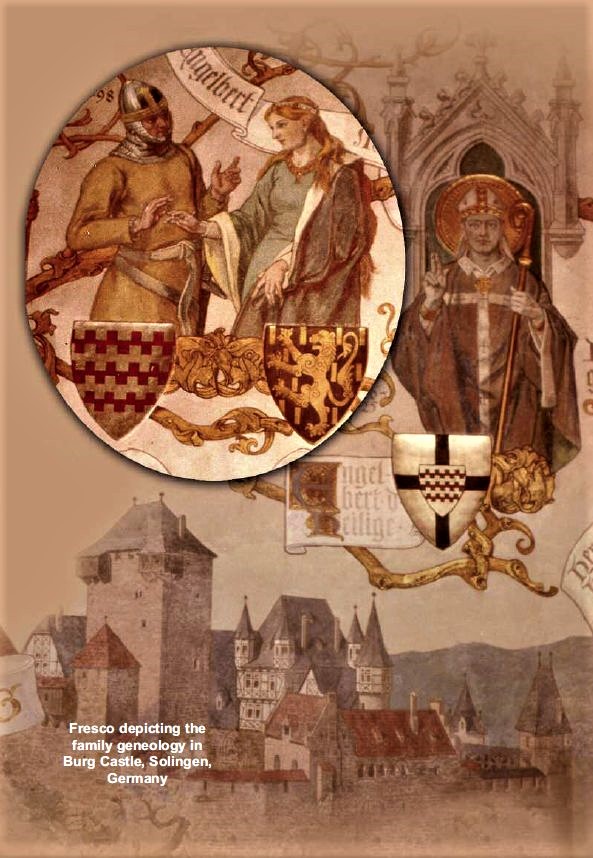

Fresco depicting the family geneology in Burg Castle, Solingen, Germany Fugitive families then started to gather around this princeps family and to constitute small social units, naturally monarchic and family-based: monarchic because of the presence of a unique and unquestionable authority; family based because it was made up essentially of the chief and his family, along with those who joined the group as newcomers but were not, properly speaking, part of the essence of that unit comprised of the chief and his family. The head of the family reigned as absolute master. He was called—this is the word to be found in documents of the period—”Sire”; his wife, the mother of the family, was called “dame,” domina. The family lived in its fortified residence. Men toiled, loved, and died in the same spot where they had been born. The head of the family was, by turns, a fighting man and agricultural worker. The lands he cultivated lay around his dwelling. Under the direction of the chief, the family became skillful in building its shelter and in making hooks and ploughs. In the inner courtyard glowed the fire of the forge in which weapons were fashioned on the resounding anvil. The women dyed and wove fabrics. The family became a fatherland, and the Latin writings of the period designated it by the word patria, and it was loved with all the more affection because it was a concrete and living fact under the eyes of everyone. It made its compelling power directly felt, as well as its gentle influence. It became a solid and well-loved defence, an indispensable protection. Without the family, man could not maintain his existence. In this way were formed those sentiments of solidarity uniting the members of the family to each other, which continued to develop and become more and more definite under the influence of a powerful tradition. A man’s prosperity contributed to that of his relatives, the honour of the one became that of the other, and, as a consequence, the shame of the one was reflected upon all the members of his kin. This formed a society to itself on a small scale, neighbour to, but isolated from, similar small societies constituted on the same model. Where is the State? It almost does not exist. The head of the family exercises all the functions proper to the State. A civilisation without the supernatural resources of the Church would have succumbed. We would have seen it crumble and the whole work come to an end. Yet, it is beyond doubt that this very disaster was largely the cause of the birth of the most extraordinary political and social regime in history: feudalism. To say that catastrophe provoked feudalism would be tantamount to affirming that the flourishing of the newborn Church was due to the persecutions: Being persecuted, Catholics reacted; on reacting, they had zeal; and with that, they dominated the old pagan world. This is an overly mechanical and simplified explanation. One cannot affirm that, first, we had a society, then a hurricane blew in and destroyed everything, then everyone gathered at remote places, and from that feudalism was born! Who could affirm that the only possible attitude of those peoples was to react and establish a living cell in each place? Who could maintain that they would necessarily give rise, in each refuge, to a man of value who would found a lineage capable of continuing his work? Who could claim they would have sufficient vigour and ingenuity to turn extremely poor lands into fertile ones and give an impulse to social renewal? Who could say they would have enough diplomatic tact, once circumstances had changed, to maintain family autonomy rather than allow themselves to be devoured by the State? * * * Before concluding this section, we should mention that “Saxon England also had a feudal system but it was less comprehensive than in France. In practice many small English landowners were ‘lordless’ and independent freemen. However, William the Conqueror introduced the more systematic and uniform type of feudalism of the Continent.”3 Furthermore, Anglo-Saxon “family institutions were identical with those of the French throughout the Middle Ages, and who, unlike the French, had continued to preserve them. Here, doubtless, lies the explanation of the prodigious Anglo-Saxon expansion throughout the world. For it is in fact, in this way, that an empire is founded, as a result of waves of explorers, pioneers, merchants, adventurers and dare-devils who leave their homes to seek a fortune, but without forgetting their native land and the tradition of their forefathers.”4

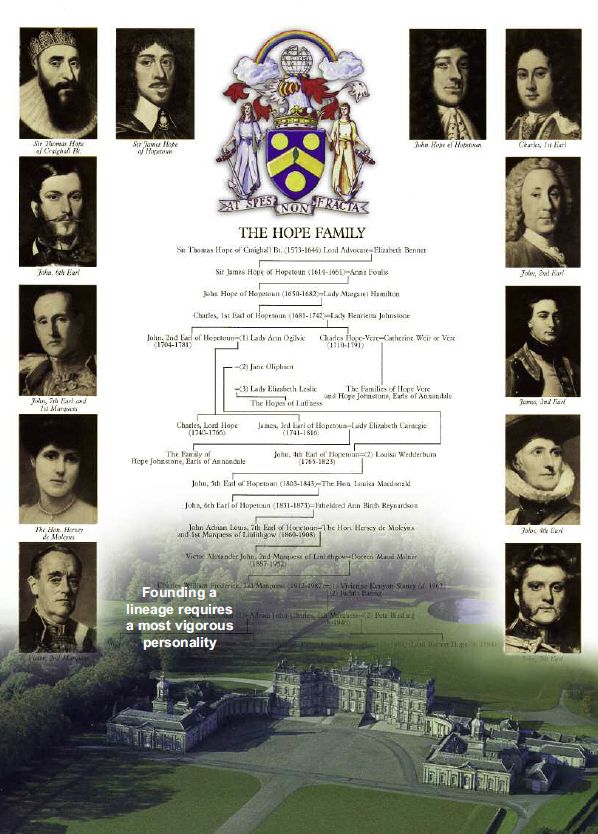

Founding a lineage requires a most vigorous personality Family Lineages: Behold What Historians Fail to Emphasise We were facing one of the primordial events in the history of mankind. When these semi-civilised tribes were pushed toward the hills and behind the swamps, a series of family lineages was born. This is a fact that historians fail to emphasise sufficiently. A lineage is something very different from a family. What is a family? It is the ensemble of father, mother, and children. It suffices to have legitimately married parents for a family to exist. A lineage, however, is quite different. The French language speaks of source, that is, origin. It refers to the source of a family just as to the source of a river. The English also used the word source in this manner, but also of stock, as in “coming from good stock”. So what is the source of a family? What is a lineageman? The founder of a lineage is a man with a vigorous enough personality to raise a family that maintains his main moral and physical hereditary traits. He gives it a sufficiently strong formation so that the initial impulse that he imparts to a certain order of things continues after him. He is a man who founds a school of feeling, of thinking, of acting, of overcoming difficulties—who founds a small system of life. I affirm that it is necessary to have much more personality to found a family lineage than to govern a country. Founding a lineage requires a most vigorous personality, one which must be vigorously wholesome in order to follow a wholesome direction. What was admirable at that moment of European history was that those families, who had been driven out, banished, and cast into utter disgrace, reacted and formed lineages all over the place who eventually became the noble lineages of Europe. These lineages, which were to mark one thousand years of history, arose from the most atrocious misfortune. Because of their natural vigour and, above all, the correspondence of their family members to God’s grace, these abandoned and isolated families gave birth to the noble family. The ensemble of these noble families then gave birth to Europe. This is the true story of feudalism. (There is a series of other facts that prepared the coming of feudalism, but we will not study them here, as this would deviate too much from our main topic.) Since lineages had such an importance in the formation of feudalism, let us study them more accurately and at length. If we have a correct concept of the family, we will know what was born when we say lineages were born. To do this, however, we need to analyse in depth the reality that is called man. Man is endowed with soul and body. Consequently, spiritual and invisible realities can be manifested to the eyes of men through visible material realities. There is a mysterious nexus between soul and body whereby the body, in some way, is a symbol of the soul. The human body is a reflection of the soul by its colour, physiognomic traits, timbre of voice, dynamism, way of moving, etc. It allows its qualities to show through. It this harmonious whole of soul and body that constitutes the human person. Thus characterised, man is susceptible of a greater or lesser physical or moral development. In the physical realm this phenomenon is known to everyone. If a newborn child is placed in an ambience in which his physical energies are stimulated, the child can grow quite large, at least as big as his nature permits; but placed in unfavourable circumstances, the child will most likely be underdeveloped. The same can be said of the soul. It has a series of potentialities that will develop if the conditions in which we place it are propitious. Otherwise, only with great difficulty would those qualities affirm themselves and triumph. We can therefore say that the human soul will develop more or less completely depending on the conditions in which it finds itself. Just as the body only realises itself fully in certain circumstances, so also does the soul. The full realisation of the human person, who is soul and body, is constituted by the full realisation of the soul and the body together. By considering this, we are better able to understand what lineage is. The family is an institution of the natural order, founded on a sacrament, and given the task of perpetuating the human species and educating the offspring. It is an institution, therefore, whose obligation is to develop and educate the human personality to the greatest possible extent. The family will perfectly accomplish its mission if it makes all the qualities of both body and soul of those born into it expand and affirm themselves completely. To accomplish this, the family is endowed with extraordinary qualities, heredity and tradition, at which we will take a closer look in Chapter 5. This notion of lineage needs to be completed. There are lineages not only in the noble class, but in all social classes. If lineage is the natural product of a family’s development, and if the family is called by the designs of Providence to develop, we must have many lineages at every level of the social hierarchy: lineages of bakers, princes, rubbish collectors, jewellers, and singers. The ensemble of these lineages is what constitutes a nation, a nation not only in the present, but with a historic continuity in the past, present, and future. Today’s Europe is the same Europe as yesterday’s because it descends from the same ancient lineages, preserving an identity of tradition. However, to the degree that these lineages fade away and are replaced by new ones without true tradition, a country is no longer the same. This is a process of many centuries. Today’s Egypt, for example, is no longer the Egypt of old, as its lineages are not the same. What was born with feudalism, both in cities and the countryside, was an enormous ensemble of men who formed lineages. This ensemble of lineages and lineagebased organisations is precisely what constituted the Middle Ages. What it had most intrinsically and deeply rooted was this structure of lineages vivified by the family spirit. This is what historians generally fail to take into account.

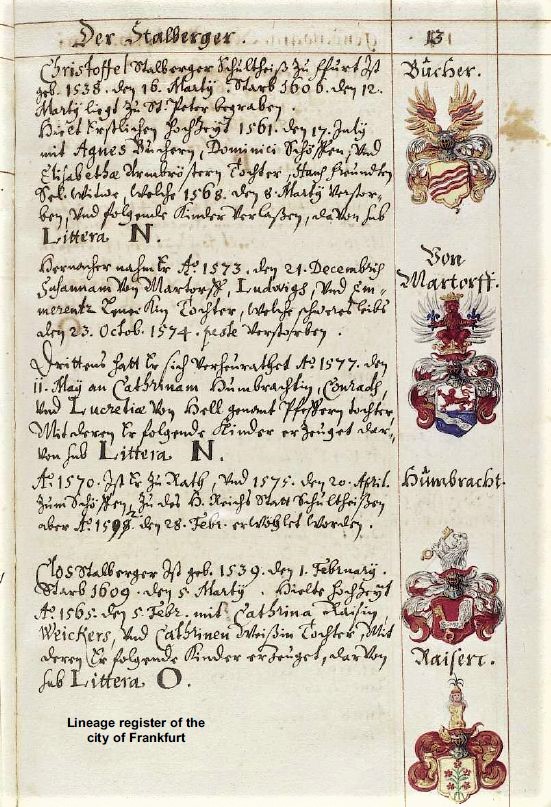

Lineage register of the city of Frankfurt Lineages and the State If a family with well-defined characteristics is spread out with many distant but very united relatives, everyone having a vivid sensation of being a member of the same family, each member will be supported by a social group independent from the State. The family is a power; as a group, it moves independently from the State and constitutes a cell with which that the State must reckon. Its members do not depend on social welfare agencies. If they become impoverished, the family will help them. Relatives form the circle of their relationships that ensures their social position no matter how they dress, etc. There is not much the State can do about institutions of this nature. If someone was born in a certain lineage, the State cannot do much about it. A defined lineage is a factor in the independence of the individual himself since it creates a barrier against State arbitrarity. In a society full of lineages, there are very important social groups that the State must take into account at every moment. Today’s society is one without lineages, with only vague or distant ties of kinship and fading families. In the feudal and medieval organisation, lineages were the raw material, but these lineages have gone through one, two, and even ten centuries of historic continuity. Note that historians unanimously agree that there are works that need to be carried out by several generations: founding certain countries, developing certain policies, creating certain sources of prosperity. The family is the institution of natural law that assures the realisation of historic works through generations. Lineage causes a dynasty to carry out a work through generations: a family of bell casters to perfect a certain type of bell, one of winemakers to produce an excellent wine, one of professors to enhance an incomparable didactic system. These are works of generations and are the most profound works in history. By natural law, they must be carried out by lineages. Families and the Justice of God Being eternal, men will be judged in life eternal; but since nations are not eternal, they will receive their reward or punishment on this earth. The same happens with families. As such they are neither saved nor lost; they are rewarded for their qualities or punished for their defects on this earth. The Scriptures many times speak about this mystery: families, called to a certain mission, who refuse and leave the stage of history; others, corresponding to grace, who begin to flourish and God makes intelligent and illustrious men to be born of them. This does not mean that every family that is impoverished is so out of punishment; but, as a general rule, one can say that the ascension or decadence of families is related to the use they make of divine grace. Thus a man ensures the continuity and ascension of his lineage by practicing acts of virtue that add up, as on a scale, here on earth. The good done by a grandfather will fall upon his grandson, and often someone’s punishment falls upon his descendant. Such is the continuity of the family, whose scale in divine justice is only one. One of the reasons for tedium in today’s family life is that families are frustrated, as are their members and conversation. One of the frustrations is that not all of the children were born—how much curse comes just from this! In a family of the Ancien Régime (French society before the French Revolution)—whether noble or plebeian, as they are all miniatures of one another, from the king’s to the poorest man’s—everyone feels and thinks the same way, everybody loves one another, the offspring is fecund, the family exists. If they go on an outing together, it is because it is natural for them to be together. With the present decadence of the family, all of that rarely takes place. If they were lineages, they would all feel that co-naturality. A comment made by one would resound in a pleasant way in all others as in a symphony. What we have today is a poor cacophony, with only a few, and, worse yet, dissonant instruments that you can barely hear any more.

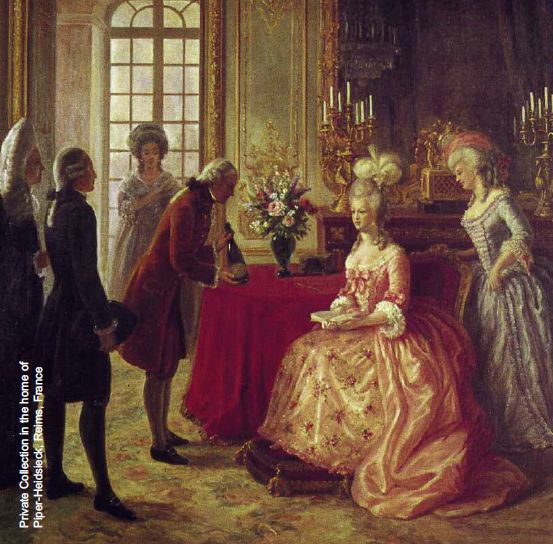

Florens-Louis Heidsieck was the son of a Lutheran minister from Westphalia. He moved to Reims to work as a cloth merchant, and discovered winemaking there. He started making his own wine in 1780, and while he was neither a viticulturist nor a native of Reims, he displayed talent and worked hard at his new-found profession. He founded his own House on 16 July 1785. He had already become an expert in his art, and even dedicated one of his wines to Queen Marie-Antoinette. Moreover, he was granted the honour of presenting it to Her Majesty in person. Lineages outside the Family Circle Finally, there can be lineages outside of the family circle. In general, great institutions are lineages not very rigorously based upon families. They constitute families of souls: religious orders, universities, or even the German army. They are spiritual lineages that can be somewhat related with natural lineages, as was the case with the German army, wherein it was traditional for certain families to occupy certain posts. They can also be unrelated, as in the cases of religious orders. These types of lineages also constituted the body social of the Middle Ages. 3) Wilfred J. Moore, Britain in the Middle Ages, G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., London, 1954, p. 78. 4) Régine Pernoud, The Glory of the Medieval World, translated by Joyce Emerson, Dennis Dobson, Ltd., 1950, p.28. |

|