|

Chapter V

7. A tribalistic and Communist conception of the mission

|

|

|

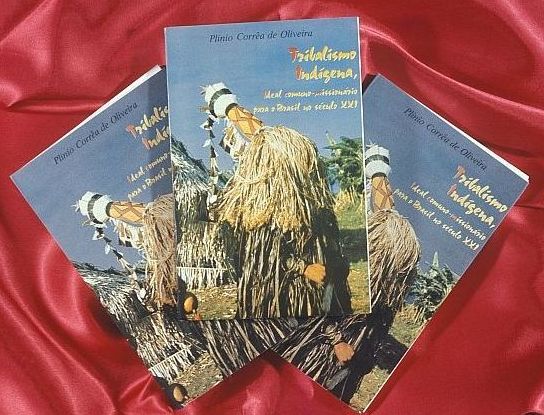

In his appendix to Revolution and Counter-Revolution Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira denounced in 1977 the birth of new “tribalistic” currents within the Catholic Church. They “intend to transform the noble, bone-like rigidity of the ecclesiastical structure — as Our Lord Jesus Christ instituted it and twenty centuries of religious life moulded it — into a cartilaginous, soft, and amorphous texture of dioceses and parishes without territories and of religious groups in which the firm canonical authority is gradually replaced by the ascendancy of Pentecostal ‘prophets’, the counterparts of the structuralistic-tribalistic witch doctors. Eventually, these prophets will be indistinguishable from witch doctors”.70 In the same year, in a book entitled Indigenous tribalism, a comunist-missionary ideal for Brazil in the XXI century,71 the Brazilian thinker analysed thirty-six documents published by the new progressivist missiology, denouncing their infiltration into the structure of the Church. By upsetting the traditional Catholic conception — according to which the aim of the Catholic missions is to bring civilization with the faith — the new missiological current saw tribalism as the chance to effect a utopian “kingdom of God” on earth. This “tribalization” process appears as the natural result of the break-up of the Christian civilization hoped for by progressivist theology. If in fact, as St Pius X affirms, no true civilization is possible outside Christianity, the denial of the civilizing mission of the Church inevitably involves regression to the tribal living of savages. “We should emphasize that the greatest problem raised by these deliria” Dr Plinio wrote “does not lie in the missionaries themselves, nor in the indians. The problem is to know how this philosophy could have arisen in Holy Mother Church with impunity, thus poisoning seminaries, deforming missionaries, and perverting missions. And all this with such strong ecclesiastical backing.”72 Two years later, when “Sandinismo” took power in Nicaragua, it seemed that the hour of victory of “liberation theology” had arrived. “The liberators” recalls Cardinal López Trujillo “transformed Nicaragua into a political testing ground they earnestly and enthusiastically supported. (…) Triumphant ‘sandinismo’ became the avant-garde of the people’s Church….”73 In Brazil, liberation theology had its media leaders in Fathers Leonardo and Clodoveo Boff, respectively a Franciscan and a Servite, protected by the cardinal of São Paulo, Paulo Evaristo Arns. At the end of February 1980 in a suburb of São Paulo, an international Congress of Theology was held. It was organized by the “Ecumenical Association of Theologians of the Third World” and brought together liberation theologians of forty-two countries, among whom were bishops, priests, religious and “committed” lay people. Cardinal Arns was nominated Honorary President of the Congress, dedicated to The Ecclesiology of Grassroot Communities. The closing session of the meeting celebrated an open apologia of the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua, by now the “theological site”74 of “liberation theology”. This homage to Sandinismo took place in the theatre of the Catholic university with the participation of the “Commander” Daniel Ortega, then the Marxist president of Nicaragua, of Father Miguel d’Escoto, of the “chaplain” of the Revolution Father Uriel Molina and of Frei Betto, the Dominican famous for the condemnation inflicted on him for terrorism. The atmosphere became almost unreal when Bishop Pedro Casaldáliga, wearing a Sandinista guerrilla uniform given to him by the Nicaraguan delegation, stated: “Dressed as a guerrilla I feel as if I had put on the robes of a priest.” Amidst applause, he then solemnly added that he would try to honour this “sacrament of liberation” with “facts, and if necessary with blood”. The TFP distributed a special issue of Catolicismo, containing a report on the “Sandinista night” and a further denunciation of Communist infiltration in Catholic circles. This was a complete illustrated report on what had happened, with the full transcript of the speeches made, followed by an introductory analysis and clear comments by Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira.75 Notes: (70) P. Corrêa de Oliveira, Revolution and Counter-Revolution, pp. 162-3. (71) Cf. P. Corrêa de Oliveira, Tribalismo indígena, ideal comuno-missionário para o Brasil no século XXI, São Paulo, Editora Vera Cruz, 1977. New caravans of the TFP, visiting 2,963 cities, distributed 76,000 copies of the book printed in seven successive editions. On “modern” missiology cf. also the essay by Father M. Poradowski on El marxismo en la teología de misiones in his book El marxismo en la teología (cit.) and by the same author, “Tribalismo y pastoral misionera”, Verbo, nos. 185-6, May-June 1980, pp. 567-578. (72) P. Corrêa de Oliveira, Tribalismo indígena, p. 48. (73) A. Lopez Trujillo, “La Teología de la Liberación: datos para su historia”, Sillar, no. 117, January-March 1985, p. 33. (74) Javier Urcelay Alonso, “Sandinismo en Nicaragua: ¿uma revolución liberadora? “, Verbo, nos. 256-60, October- December 1987, pp. 1171-92. Cf. also Nicaragua. Les contradictions du sandinisme, edited by P. Vayssière, Paris, Presses du CNRS, 1988. (75) Cf. Catolicismo, no. 355, July-August 1980. |

|